On 8 September 2016, the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) hosted an FKP Seminar in which two studies related to energy were presented. The first presentation was by Sonny Mumbunan (Research Center for Climate Change Universitas Indonesia, RCCC UI), on “Stranded Assets, Carbon Risks and Coal Mines in Indonesia.” As a background to the study, it is worth to note that the Paris Agreement for parties (including Indonesia) under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is committed to pursuing efforts to limit the Earth’s temperature increase to 1.5 °C. This results in a condition where coal becomes a carbon constraint, causing the price of coal to plunge, and leading some assets to become financially stranded, in the sense that they lost economic value as a result of an unforeseeable regulatory. Towards this end, the study looks at the impact of carbon risks of stranded assets in Indonesia. In terms of methodology, the study uses cash costs to be the assumed type of cost, where the market value of a coal company is determined by the remaining expected life of the mine company, effective discount rate, and the company’s annual income (total revenue of production deducted by stripping and processing costs of coal mine).

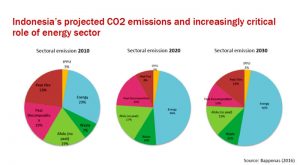

The study found that 83% of coal production in Indonesia had been for export, and that the carbon constraint set by international coal market has resulted in the declining price of Indonesian coal exports. As a result, Indonesia’s coal companies are operating at, near, or below their marginal costs. To cope with stranding assets, Indonesia’s coal companies has been putting efforts through expanded domestic consumption, such as the 35 Giga Watt Electricity Project, which could later stimulate the price of coal. On the other hand, coal-based power plants have proposal for price subsidies in a form of cost-based pricing. The findings have several implications. First, coal may remain dominant in Indonesia’s energy mix, that there are several approaches to stranded assets problem. Second, the state may have the most to lose from stranded assets. Finally, the national emission reduction efforts have yet to factor in economic and fiscal implication of stranding assets from fossil fuels and especially coal.