FKP hosted by The SMERU Research Institute with Umbu Reku Raya (Independent researcher). Thursday, 20 July 2023.

KEY POINTS:

- Does promoting social inclusion reduce inequality in development outcomes in caste-based societies in Bali and Sumba? In Bali, a shift in political power from the upper caste to the lower caste, starting in 1965/66, resulted in a significant political shock. This led to increased freedom for the lower caste, who experienced less direct control over their daily livelihood. The transition from agriculture to the services sector, driven by tourism, was considered more “caste blind,” contributing to reduced discrimination and inequality in development outcomes.

- However, in Sumba, the shift in power was limited to the Nobility and Commoner castes, excluding the enslaved caste from gaining political power and freedom. The persistence of indigenous slavery and the lack of democratization without addressing slavery abolition hindered the reduction of inequality in development outcomes in Sumba. Addressing freedom/slavery abolition and introducing political and economic shocks are essential to promoting social inclusion and reducing inequalities in this context.

SUMMARY

-

- Does promoting social inclusion – measured as shifts in local political power from the upper caste to the lower caste – reduce inequality in development outcomes in caste-based societies in Bali and Sumba? Ancient institutions such as caste and indigenous slavery can create persistent unequal opportunities for development within the practicing society.

- Social inclusion, the shifts of power from the upper caste to the lower caste, can suppress the ability of upper caste to discriminate against the lower caste – reducing gaps in development outcomes. Most studies in India context is on caste-based affirmative action and not on shift of power in local government. Societies in Bali and Sumba subscribe to the Austronesian caste system, which is simpler than the Indian caste (and jati) system. The caste system in Sumba still has elements of indigenous slavery; the caste system in Bali no longer has that element.

- Umbu Reku Raya (Independent researcher) and Budy P. Resosudarmo (The Australian National University) in their study shows that in Bali, the shift in power that started in 1965/66 was a big political shock. The lower caste has freedom because they live ”outside the wall” of the nobility residence. No direct control on their daily livelihood compared to the lower caste in Sumba. Since the 1970s there was a shift from the agriculture sector to the services sector driven by the tourism sector. The tourism sector is more ”caste blind” than the agriculture sector.

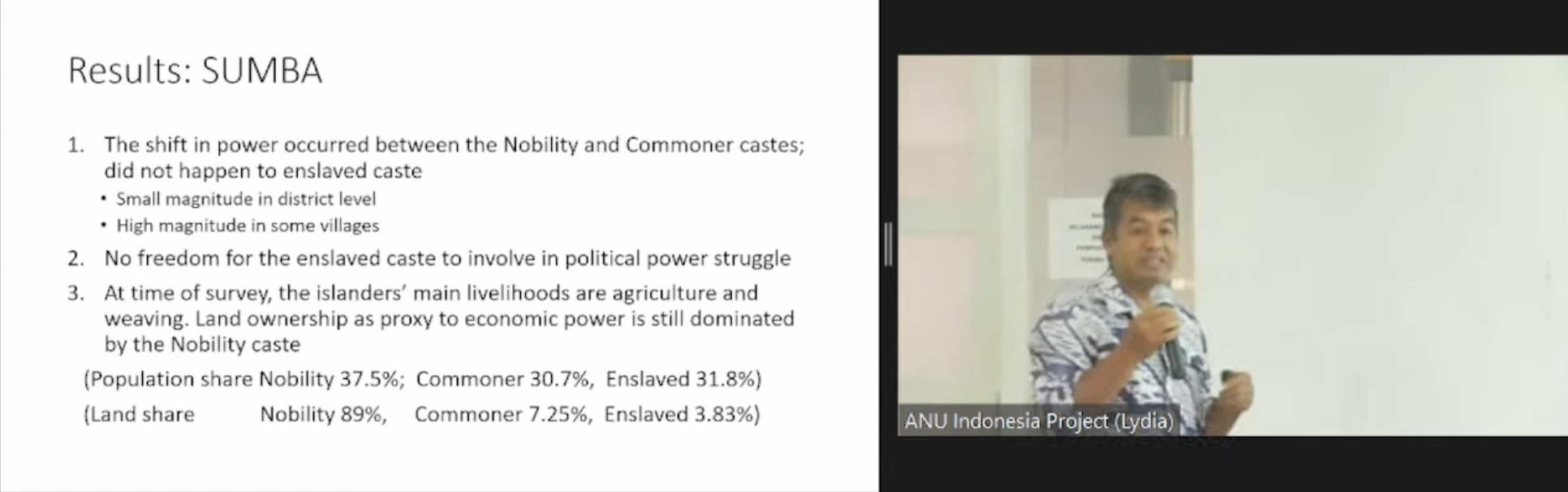

- In Sumba, the study shows that the shift in power only occurred between the Nobility and Commoner castes. It did not happen to the enslaved caste. No freedom for the enslaved caste to be involved in political power struggle. At time of survey, the islanders’ main livelihoods are agriculture and weaving. Land ownership as a proxy to economic power is still dominated by the Nobility caste.

- Political power gives advantage in human capital (educational attainment in Bali and Sumba, and body height in Sumba) of the ruling caste. Promoting social inclusion via inter-caste power shift is good for reducing inequalities of development outcomes. Sumba in 2015 had a higher education gap compared to Bali in 2002. As of 2015, the two lower castes and especially the enslaved caste in Sumba lack freedom, political power, and economic power compared to the lower caste in Bali in 2002. Democratization without slavery abolition does not benefit the lowest enslaved caste, enslaved people seem to “prefer” to stay with their masters to secure fulfillment of some basic needs. There is a need for freedom/slavery abolition and also political and economic shocks in Sumba.