The status of minority groups in Indonesia has fluctuated over time. In recent years, Indonesia’s “unity in diversity” motto has been a subject of scrutiny, especially regarding the state and community’s attitude towards religious, ethnic, and sexual minorities. The complexities of this topic are explored in the 2019 Indonesia Update Book entitled Contentious Belonging: The Place of Minorities in Indonesia, which was published by ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. The book was launched in collaboration with the Center of Politics of the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) on Wednesday, 31 July 2019 at Gedung Widya Graha, LIPI, Jakarta.

The status of minority groups in Indonesia has fluctuated over time. In recent years, Indonesia’s “unity in diversity” motto has been a subject of scrutiny, especially regarding the state and community’s attitude towards religious, ethnic, and sexual minorities. The complexities of this topic are explored in the 2019 Indonesia Update Book entitled Contentious Belonging: The Place of Minorities in Indonesia, which was published by ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. The book was launched in collaboration with the Center of Politics of the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) on Wednesday, 31 July 2019 at Gedung Widya Graha, LIPI, Jakarta.

Professor Dewi Fortuna Anwar (LIPI) officially launched the book officially. In her remarks, Professor Anwar discussed some ideas discussed in the book. Empirical evidence showed that Indonesia’s democracy has shifted from stagnation to regression in recent years. Indonesia prides itself as a tolerant, pluralistic Muslim-majority country, yet major human rights organizations have recently castigated this image of Indonesia due to the country’s decline in human rights protection, especially for minorities. The findings of this book calls not only the question of where democracy is heading in Indonesia, but rather where Indonesia is heading, as this is not just a matter of governance. Professor Anwar emphasized the importance of increasing access to this book, and therefore hopes that the book would be translated to Indonesian so that it will reach the general public and policy makers.

Professor Dewi Fortuna Anwar (LIPI) officially launched the book officially. In her remarks, Professor Anwar discussed some ideas discussed in the book. Empirical evidence showed that Indonesia’s democracy has shifted from stagnation to regression in recent years. Indonesia prides itself as a tolerant, pluralistic Muslim-majority country, yet major human rights organizations have recently castigated this image of Indonesia due to the country’s decline in human rights protection, especially for minorities. The findings of this book calls not only the question of where democracy is heading in Indonesia, but rather where Indonesia is heading, as this is not just a matter of governance. Professor Anwar emphasized the importance of increasing access to this book, and therefore hopes that the book would be translated to Indonesian so that it will reach the general public and policy makers.

Next, Ronit Ricci (The Australian National University), who is one of the editors of the book, discussed the question of minorities from a different perspective. Rather than studying minorities in Indonesia, she is studying Indonesian minorities elsewhere. For many years, Ricci has been studying Indonesian descents in Sri Lanka who were exiled from Nusantara during the colonial era. This group, who mostly practices Islam and speaks Malay, is considered a tiny minority in Sri Lanka’s population, the majority of which are followers of Buddhism and Hinduism and speak Sinhala and Tamil. This study goes to show how complicated the issue of minorities is, as a group can become a majority in one place and a minority elsewhere. This also raises the question of what exactly is the meaning of a minority—a question that is often overlooked because we are used to think of it in quantitative terms. But numbers do not tell the whole story; a minority in one point of time can become a majority; an individual can be a minority in one of their identity categories, but not in others. Last, Ricci emphasized the importance of language that is used to refer to particular minorities, for it creates and maintains certain ideas and impact minorities’ sense of belonging (e.g. the use of “pribumi” vs “non-pribumi”, “kubu” vs “orang rimba”, etc.). She asserted that the use of language constitute meaningful definitions for those using and are addressed by them. Not only do they reflect changing times, they can also create change.

Next, Ronit Ricci (The Australian National University), who is one of the editors of the book, discussed the question of minorities from a different perspective. Rather than studying minorities in Indonesia, she is studying Indonesian minorities elsewhere. For many years, Ricci has been studying Indonesian descents in Sri Lanka who were exiled from Nusantara during the colonial era. This group, who mostly practices Islam and speaks Malay, is considered a tiny minority in Sri Lanka’s population, the majority of which are followers of Buddhism and Hinduism and speak Sinhala and Tamil. This study goes to show how complicated the issue of minorities is, as a group can become a majority in one place and a minority elsewhere. This also raises the question of what exactly is the meaning of a minority—a question that is often overlooked because we are used to think of it in quantitative terms. But numbers do not tell the whole story; a minority in one point of time can become a majority; an individual can be a minority in one of their identity categories, but not in others. Last, Ricci emphasized the importance of language that is used to refer to particular minorities, for it creates and maintains certain ideas and impact minorities’ sense of belonging (e.g. the use of “pribumi” vs “non-pribumi”, “kubu” vs “orang rimba”, etc.). She asserted that the use of language constitute meaningful definitions for those using and are addressed by them. Not only do they reflect changing times, they can also create change.

Greg Fealy (The Australian National University), who is also the editor of the book shared the background leading up to the topic. The topic of minorities is chosen because it is felt to be the right time. In the last decade Indonesia has branded itself as a moderate, Muslim majority democracy that values diversity and pluralism. However, there has been running scrutiny and criticism about Indonesia’s treatment of minorities, particularly its religious and sexual minorities. Fealy went on to discuss some chapters in the book about the Chinese community and the Orang Rimba. In many ways, Indonesian Chinese communities are in better position than 30 years ago in the New Order era as we now have ethnic Chinese people in the cabinet and parliament, publications under Chinese names, etc. However, the case of Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (i.e. Jakarta’s former governor) showed that being Chinese can be a vulnerability in politics. Similarly, the government of Indonesia has also shown some progress in recognizing the rights of Orang Rimba. However, they are still expected to fit into a certain pattern of behaviour and social life, which leads to the marginalization. Concluding his remarks, Fealy expressed that before branding itself as a model of a Muslim-democracy, Indonesia needs to make sure that we live up to those claims.

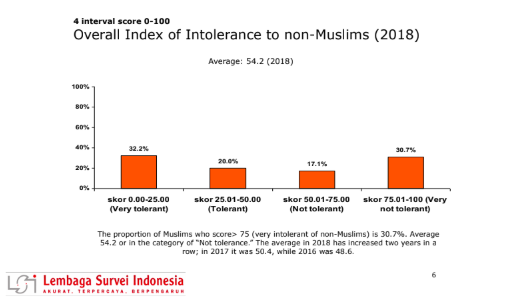

Burhanuddin Muhtadi (UIN Jakarta) shared his chapter which is based on a study conducted in collaboration with the Indonesian Survey Institute (LSI). Using multi-year data series, the study sought to understand the Islamist mobilizations during Basuki Tjahaja Purnama’s blasphemy allegation case. The study found that the proportion of Indonesian Muslims who are deemed very scored ‘very intolerant’ towards racial and religious minorities has constantly expanded from 2016 to 2018. Muslim intolerance towards non-Muslims is also found to be higher than non-Muslim intolerance towards Muslims. Both Muslim and Non-Muslim citizens who perceive themselves as a part of the majority also report a higher level of intolerance than those who do not. Based on this survey, Murhanuddin also found that the increase in intolerance only arose after the anti-Ahok protests. In conclusion, the recent rise in intolerance was not a mobilizing factor, but rather mobilized by religio-political entrepreneurs.

As one of the discussants, Professor Asvi Warman Adam (LIPI) gave some suggestions of other minority groups that could be included in the book. The concept of being a minority in Indonesia ranges from various perspectives, including historical, legal, political, cultural, discursive, and social. The first group that Professor Adam suggested was the victims of 1965 anti-communist purge. Political exiles, those who were accused of being communists, as well as their families have been excluded from the society, constantly monitored, and was the target of the state’s discriminative regulations. Next, he also looked to the place of Confucianism in Indonesia. Although it is one of the six officially accepted religions in Indonesia, Confucianism do not have a general directorate in The Ministry of Religion, due to the small number of Confucians in Indonesia. Considering its size, he stated that in around 10 years, Confucianism may no longer exist in Indonesia. Professor Adam also slightly touched the topic of interfaith marriages in Indonesia and the long existence of people with varying sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expressions in Indonesia.

Lastly, Professor Firman Noor (Head of the Center for Politics LIPI) also shared his thoughts on the book. He expressed that the current setback in Indonesia’s democracy is something that every major democracies had gone through in the past. The fact that the topic of minorities have surfaced prove that Indonesia is in transition to an advanced democracy, since the discussion of these topics were unimaginable 20 years ago. In response to the multifaceted nature of the topic, Professor Noor reminded the audience of the existence of different subsections within a minority group. He looked to the example of Medan Chinese, who face negative stigmas among the Indonesian Chinese community. He also pointed out how the book did not see Islamic extremist groups as a minority group among Indonesian Muslims. These generalizations can give a false portrayal of minority groups as monolithic. Professor Noor also questioned the definition of intolerance by using the example of Papua’s special authority (Otsus), in which the leaders have to be indigenous Papuans. He argued that sometimes, having particular preferences about a leader is an expression of the people’s rights. Even though what happened in Jakarta is regretful, a recent survey showed that Jakarta’s democracy index is the highest in the country. This shows that a single portrait does not necessarily reflect the big picture that is actually happening.

For the complete presentation and Q&A session, please refer to the video and materials provided.