Violence against women is a problem that is still rampant in Indonesia. Not only does this violate women’s fundamental rights, it is also a factor that hinders women’s participation in a country’s development. On Thursday, 10 October 2019, The SMERU Research Institute hosted an FKP event at the Jakarta City Hall. The speakers were Imiarti Fuad (Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection of the Republic of Indonesia or KemenPPPA), Azriana R. Manalu (National Commission on the Elimination of Violence against Women or Komnas Perempuan), Tuty Kusumawati (Department of Child Protection, Empowernment, and Population Control, DKI Jakarta), and Veni Siregar (Forum Pengada Layanan).

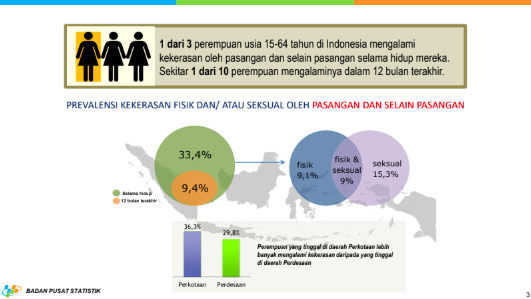

Beginning to session, Imiarti Fuad presented the results of The National Survey of Women’s Living Experience, which was conducted by KemenPPPA. This survey defines violence against women as any action that is based on gender differences that may result in women’s physical, sexual, or psychological suffering, whether in the public or private spheres. The data shows that 1 out of 3 women aged 15-64 in Indonesia has experienced gender-based violence in their lifetime. For ever-married women, the most common form of violence is forced sexual intercourse by their spouse. As a response to this issue, the local government of DKI Jakarta has established a local unit for women and child protection, which provides services in the likes of a reporting system, victim outreach, case management, temporary shelter, mediation, and victim assistance. To improve these services, Imiarti calls for the optimization of data on sexual violence, local regulations, and coordination between the local government with like-minded institutions.

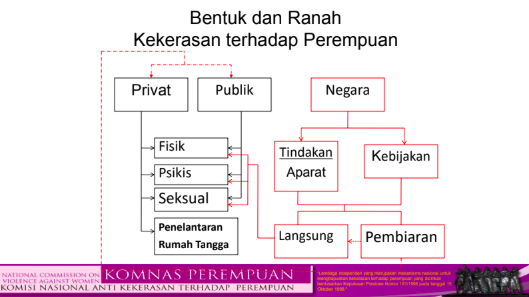

Next, Azriana R. Manalu elaborated the historical development of violence against women in Indonesia. Azriana asserts that gender-based violence is a matter of imbalanced power-relations. Therefore, the recovery victims of violence must require interventions within the realms in which violence is happening: family, community, and country. A majority of gender-based violence happen within the family in the form of psychological violence. In public sphere, most of the violence is sexual. As for the patterns and tendencies of violence against women in the realm of the state, it includes the criminalization of women through regulations on prostitution, pornography, and other morality-based issues. From a regulatory perspective, challenges to overcome this issue include the limited ability of current laws to recognize the breadth of violence against women, especially sexual violence, the perception of gender-based violence as a “sectoral” issue, and gender-blind data. Socially, cultural practices that discriminate women have yet to be fully eradicated, and morality are increasingly politicized.

Tuty Kusumawati explained DKI Jakarta’s effort in preventing and dealing with violence against women. Within 2016-2019, the trend of violence against women and children has decreased in Jakarta, but the efforts to reduce the number even further are still administered. The Jakarta Provincial Government Regulation No. 8 of 2011 comprise of a comprehensive 26-point action plan, which include the provision of information on violence against women and children (physical campaigns, social media, mass media, etc.); the optimization of rights and protection of female workers and the minimization of child labor; family education programs to prevent and overcome violence in the family; violence reporting services; integrated service center for victims; medical report (visum) service for victims of violence in state-owned hospitals; safe houses for victims; and economic empowerment programs for victims, among many others.

Lastly, Veni Siregar shared about the current state of access to Justice and services for victims of violence in Indonesia. Veni explained that recovery services in Indonesia still needs improving. From the reporting stage, law enforcement officers are often act unfavorably towards victims. Many cases also end up being forcibly reconciled without proper legal settlements. Regarding access to medical and psychological services, costs of medical reports and treatments, as well as the limited number of medical and psychological personnel pose and binding constraints. In addition, shelters or safe homes are limited and victims have limited access to economic empowerment programs or even paid leaves from work during their recovery time. From a legal perspective, the Indonesia’s current Criminal law and non-criminal law code (KUHP and KUHAP) are inadequate to deal with gender-based violence. Some laws even have the potential to criminalize victims (e.g. Law on Information and Electronic Transactions or UU ITE and Pornography Law). These conditions are made worse by the current view on gender-based violence as a disgrace and may cause victims to be socially excluded.

For the complete presentation and Q&A session, please refer to the video and materials provided.