Despite women’s increasing participation in the work force, female workers are still disproportionately subjected to household and care duties in comparison to their male counterparts. Aside from having to constantly negotiate between the two, middle-class women often resort to hiring babysitters. On Thursday, 29 August 2019, Lembaga Demografi FEB UI hosted the last FKP event of the month regarding this phenomenon. Two researchers presented their studies. First, Diahhadi Setyonaluri (Lebaga Demografi FEB UI) presented her study, which was conducted with Ariane Utomo (University of Melbourne) on Jakarta women’s negotiation between work, family, and the traffic. This was followed by a presentation by Gita Nasution (Department of Anthropology, The Australian National University) on the emerging occupation of babysitters in urban Indonesia.

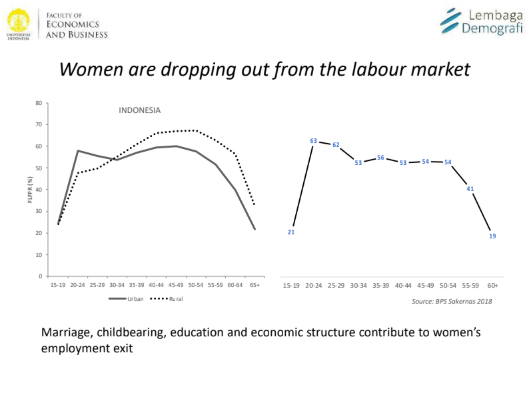

Diahhadi Setyonaluri began the seminar by showing how Indonesian women are dropping out of the labor market at the time they bear children, and return after the children are grown up. This risk of leaving employment varies among different occupations, sectors, and education levels; women in sales and service who have weaker job security, in the private sector, and only completed secondary education have a higher risk in dropping out from the labor market. Additionally, gender asymmetry in work and care is still prevalent in Indonesia. Caregiving is often perceived as the responsibility of women, which brings about the financial and time constraints for working women.

Taking into account gender asymmetry, marriage and fertility norms, and the absence institutional support, this study centers its analysis on women’s opportunity costs to work. These opportunity costs vary among women based on resources (access and quality of childcare), class resources (education), and contextual factors (Jakarta’s traffic). Through semi-structure interviews and a focus group discussion of 30 women living in the Jabodetabek area with varying backgrounds, this study found that time spent on commuting amplifies women’s opportunity costs to work. However, the availability of trusted care could offset the costs. For this reason, Diahhadi suggests the fine-tuning of work policies to allow family-friendly and flex-work arrangements; ensuring the provision of childcare for the poor; and providing integrated and reliable mass transport system to reduce the opportunity costs to work faced by women in Jakarta.

Taking into account gender asymmetry, marriage and fertility norms, and the absence institutional support, this study centers its analysis on women’s opportunity costs to work. These opportunity costs vary among women based on resources (access and quality of childcare), class resources (education), and contextual factors (Jakarta’s traffic). Through semi-structure interviews and a focus group discussion of 30 women living in the Jabodetabek area with varying backgrounds, this study found that time spent on commuting amplifies women’s opportunity costs to work. However, the availability of trusted care could offset the costs. For this reason, Diahhadi suggests the fine-tuning of work policies to allow family-friendly and flex-work arrangements; ensuring the provision of childcare for the poor; and providing integrated and reliable mass transport system to reduce the opportunity costs to work faced by women in Jakarta.

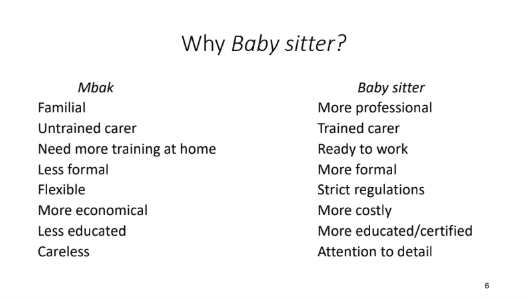

Next, Gita Nasution presented her study on the emergence of babysitters as an occupation in Indonesia. As a response to the increasing number of women in the work force, middle and upper class women resort to various forms of care providers, which include professional babysitters and familial domestic workers (PRT). In choosing the type of care providers, female employers highly value experience, familial relationship, and flexibility. Babysitters are considered more formal, trained/educated, have stricter regulations, and are more costly compared to PRT. However, babysitters also expect flexibility at work, generosity of employers, and the opportunity to pursue personal aspirations (e.g. family, income, higher education). Sometimes, these expectations do not match and cause conflicts. As a result, in addition to babysitter agencies’ role as a supplier and trainer, they also play the role of the mediator between employers and babysitters.

Gita also presented other characteristics of babysitter as a profession. A noticeable feature among Indonesian babysitters is their uniforms. Aside from a symbol of professionalism, this can be seen as a differentiation of class/hierarchy between the employer and the babysitter. Gita also found that babysitter as a profession are still seen as domestic work – on one hand, babysitters are usually trained and certified, but they are also working in a house under the employer’s domain. This work is also gendered; most babysitters are women, whereas men usually work in the agencies or as trainers for these babysitters. All in all, the emergence of babysitter as a profession display Indonesia’s persisting class and gender relations in the public sphere.

Gita also presented other characteristics of babysitter as a profession. A noticeable feature among Indonesian babysitters is their uniforms. Aside from a symbol of professionalism, this can be seen as a differentiation of class/hierarchy between the employer and the babysitter. Gita also found that babysitter as a profession are still seen as domestic work – on one hand, babysitters are usually trained and certified, but they are also working in a house under the employer’s domain. This work is also gendered; most babysitters are women, whereas men usually work in the agencies or as trainers for these babysitters. All in all, the emergence of babysitter as a profession display Indonesia’s persisting class and gender relations in the public sphere.

For the complete presentation and Q&A session, please refer to the video and materials provided.