The quality of human capital and the dominance of informal sector jobs are some of the biggest challenges for Indonesia’s labor market. What factors influence the development of human capital in Indonesia? What are the links between formal and informal sectors in Indonesia? These topics were discussed in a the FKP event hosted by SMERU Research Institute on 25 October 2018. Daniel Suryadarma (The SMERU Research Instttute or SMERU), Devanto pratomo (Universitas Brawijaya), and Rashesh Shrestha (Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia or ERIA) shared the findings from their respective research.

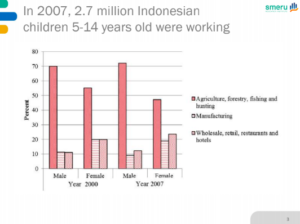

Daniel Suryadarma (SMERU) began the discussing by presenting a research on the effects of child market work on human capital accumulation. Although the percentage of child labor in Indonesia is relatively small, the absolute number is still considerably high. In 2007, 2.7 million children in Indonesia work, many of which work in hazardous sectors such as mining and construction. However, unlike many other developing countries, most of the work is done inside the household, as opposed to outside the household in the manufacturing sector (e.g. India). Using Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS) data, Daniel found that child market work does not affect the years of schooling and cognitive skills. However, it is evident that child market work adversely affects a child worker’s mathematical skills by an equivalent of three years of schooling, as well as lowering their lung capacity. These effects may harm a child’s future earnings. All in all, child market work is seen as a trade-off between current and future income.

Devanto Pratomo (Universitas Brawijaya) continued the session with a presentation of his research with Chris Manning (The Australian National University) on the role of job transitions in supporting the growth of formal sector jobs. Indonesian labour market has shifted from mostly informal workers from the agriculture sector into the formal sector. Using the National Labour Force Survey (Survei Angkatan Kerja Nasional or SAKERNAS), Pratomo and Manning’s research found that the growth of the formal sector is the result of the entrance of new and better-educated workers rather than the transitioning of informal workers into the formal sector. Pratomo and Manning also found that mobility to the formal sector happens more by workers with characteristics that are similar to those in the formal sector. Moreover, individuals who move from one formal job to another also earn more than new entrants or those who move to the formal sector from the informal sector.

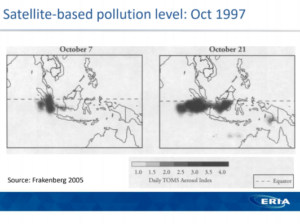

Finally, Rashesh Shrestha (ERIA) shared his research regarding early life exposure to air pollution, cognitive development, and labor market outcomes. The 1997/98 forest fires affected around ~70 million people, mostly in Sumatra and Kalimantan. Using data from the 2014 IFLS, Shreshta tried to infer the long-term effects of this external shock in early life (in utero) by conducting a two-step approach: assessing the relationship between air pollution exposure and cognitive ability, and that between cognitive ability and future earnings. Based on this research, he found that fetuses with pollution exposure are found to have 1 whole point lower in their cognitive scores, which are consequently correlated to a 2.8–5.3% negative effect on future earnings due to air pollution.

For the complete presentation and Q&A session, please refer to the video and materials provided.