FKP hosted by ANU Indonesia Project with Robert Sparrow (Wageningen University) and Sirojuddin Arif (The SMERU Research Institute). Thursday, 4 March 2021.

KEY POINTS:

- Due to economic development and globalization, people’s lifestyles and diets in Indonesia change towards more processed foods. This paper wants to understand the behavioral mechanisms that could help policymakers in defining policy responses, in particular the information and behavioral nudges of healthy food choices by children.

- Nudges are effective in altering children’s snack choices. Cognitive nudges can help improve healthy choices but their effect is relatively small in the social context. Unhealthy food in the market may stimulate unhealthy food choices and influence others. On the other hand, healthy eating peers have little influence and this does not interact with information provision. This would suggest that a more paternalistic intervention on the food environment in the neighborhood or schools is needed.

SUMMARY

- Indonesia faces the double burden of malnutrition (stunting and overweight) and due to economic development and globalization, people’s lifestyles and diets in Indonesia change towards more processed foods (dense in calories, fat, and sugar) and fewer grains, fruits, and vegetables. With that comes also the increased risk of non-communicable disease, especially for children.

- The aim of this study is to understand the behavioral mechanisms that could help policymakers in defining policy responses, in particular the information and behavioral nudges of healthy food choice. Information on healthy nutrition (e.g., education, media) is a key element of many health interventions, but the effectiveness of information in changing peoples’ behavior is still unclear. Over the last decades, nudges (giving people little incentives to change their behavior, popular in behavioral economics) are widely used for influencing dietary choices. Nudges are attractive for policymakers because of their low cost and intuitiveness, especially for the interventions targeted at children. However, nudges do not operate in a vacuum: children are exposed to other signals, for instance a child’s peers may also influence nutrition choices. Therefore, the experiments wanted to look at how these factors affect children’s healthy food choices (information, nudges, and social environment).

- The study evaluated the influence of a cognitive nudge that may trigger children’s automatic take-up of healthy/unhealthy snacks. The study also explored how peer behavior may account for spillover effects in driving children’s preferences towards particular foods. Lastly, the efficiency of information was revisited by assessing the differences of the two nudges by variation in information provision. The nudges were provided by the effect of affective (emoji labels) and social (peer behavior) nudges on primary school children’s snacking behavior in Jakarta. The study then looked at the heterogeneity of these effects depending on their prior educational information about healthy eating.

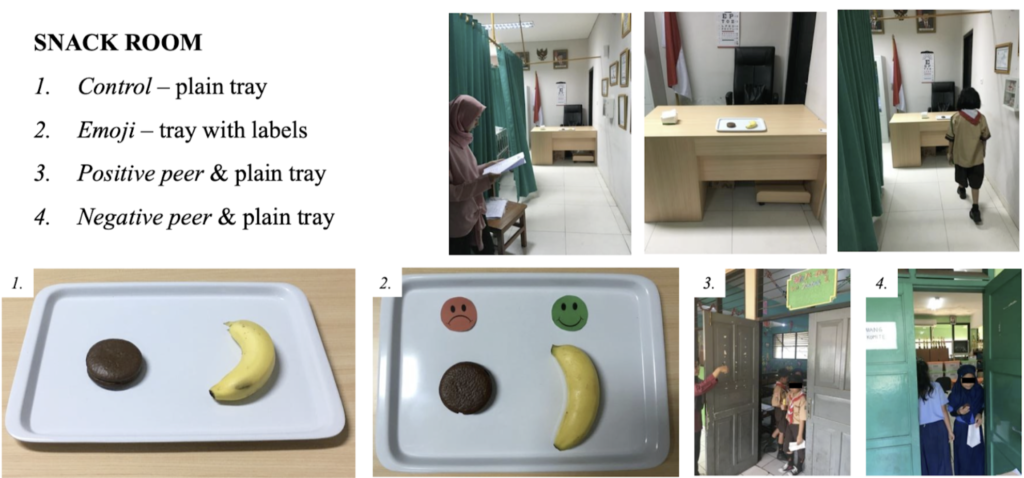

- The behavioral field experiment was conducted in 18 public primary schools in Central Jakarta (1673 children of 6-13 years old). There were two snacks offered: healthy (banana) and unhealthy (choco-pie), these two snacks were chosen based on their comparability in terms of the price, size, and availability (comparable substitutes). Given that choice, randomized exposures to cognitive and affective nudges were given to 4 different groups.

- Control: Not exposed to nudges/information, no labels/peers.

- Emoji: Exposed to affective nudge in form of “smiley” emoji labels next to the respective snack options.

- Positive peer: Before the children enter the room to make a choice, they would see a classmate leave the room with a banana (healthy food)

- Negative peer: Before the children enter the room to make a choice, they would see a classmate leave the room with Choco-pie (unhealthy food)

- The study also randomized the exposure of groups of children to educational videos on healthy eating to look at the effect of information on their decision (cognitive nudges). Each student/child would be asked to come to a room to choose a snack presented on a tray (as shown in the picture below).

- The main result shows that from the group without the educational video, more than 60% in the control group chose bananas. Those that were exposed to emoji, would increase about 10% more than the control group. Those who were exposed to positive peers choose bananas slightly more, but not at a statistically significant level. But then for the negative peer, a large drop in bananas is observed, with about 65% of students choosing choco-pie.

- With the educational video, the healthy choice is higher across the groups. Now 84% of the control group chose bananas. The proportion who chose a banana in the other groups were 92% in the emoji group, 88% in the positive peer group, and 48% in the negative peer. However, again a positive peer does not have a statistically significant impact. Also, there are no significant differences in educational video interactions with the nudges on healthy food choices.

- In conclusion, nudges are effective in altering children’s snack choices. The positive effect of evaluative labels (emojis) shows a 21% higher number of kids who opted for a healthy snack. The negative effect of a social nudge (unhealthy peer’s choice) shows 44% fewer kids chose a banana, much larger than the positive effect. However, educational information may work since a 21% point increase of a healthy snack choice was observed for those who watched the information video, but no interaction with the nudges was observed (information and nudges work separately).

- So far, the relation between nutritional knowledge and eating behavior is inconclusive. This study also confirms the mixed impact of information on behavior. Some studies found that knowledge and behavior is unrelated. But others suggest that from social cognitive theory, nutrition education works. Some also say that nutrition education improves knowledge, but no significant impacts on dietary diversity. However, there might be other significant factors, food availability and parental modelling effects may have a strong impact on the choices.

- The implication of these findings is that cognitive nudges can help but compared to adverse peer effects their effect is relatively small in the social context. Unhealthy food in the market may stimulate unhealthy food choices and influence others. Also, healthy eating peers have little influence and this does not interact with information provision. The implication is that healthy eating “ambassadors” may not help kids to eat healthily. This would suggest that a more paternalistic intervention is needed to adjust the food environment in the neighborhood or schools, rather than rely on the individual’s decision after giving them information or nudges.

- In his discussion of the paper, Sirojuddin Arif raised the issue that Indonesia is ranked very low in terms of food diversity. For example, the lack of fruit and vegetable consumption is common in Indonesia, including Jakarta, where less than 5% of children 5 years or older consume the WHO recommended daily intake of fruits and vegetable. Indonesian government is currently implementing national information campaigns; given the result of this experiment, we can then ask: under what condition are knowledge and behaviour related, and how should this inform the government campaign policy? Further, the government campaigns are mostly directed at adults (parents, educators, etc) in which case, it would be helpful if the research can shed more light on how parents actually affect their children’s choice and what strategies can be taken to mitigate the negative peer effect. Finally, he also raised the policy implication of this study, given institutional weaknesses in the form of overlapping jurisdictions between the education and health services at the local government level.