On 24 October 2017, Valentina Y. D. Utari (SMERU Research Institute) presented a study conducted by her team entitled “Unpaid Care Work in Indonesia: Why Should We Care?” at the fourth FKP Seminar in October hosted by SMERU Research Institute. The study is an independent work intended as a continuation of a global study started in 2012 and organized by the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA).

Care work is basically a term referring to activities that involve direct caring, such as nursing the sick, taking care of the elderly and so on, and indirect caring, which are housekeeping, home management and the like, preparation of clothing, and many more. The word ‘unpaid’ is added to portray the prevailing practice of not assigning monetary value to care work, which are most of the time carried out by women, particularly within families and communities. Utari argued that raising awareness of this issue was essential to achieve gender equality, rights-based human development, and welfare, which was are parallel objectives within the international Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Indeed, unpaid care work is an issue that is heavily related to gender equality since data from previous study by SMERU Research Institute reveals that over 45% of caring responsibility was transferred from mothers who became migrant workers, to their mothers or mothers-in-law, this is 7% higher than transfer of care responsibilities to their husbands.

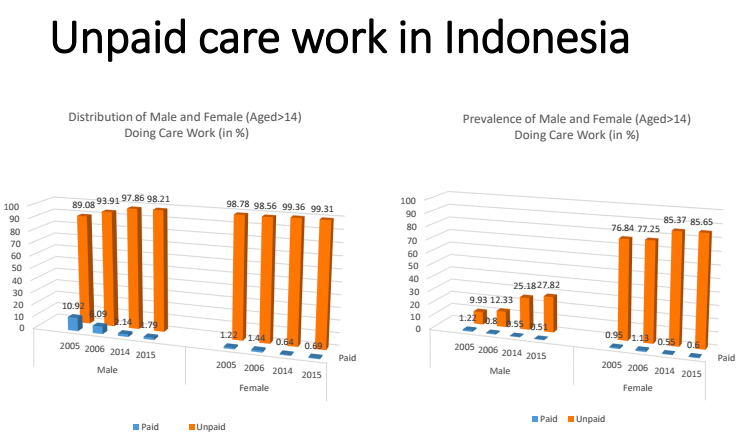

Utari and her team combined desk study and visual methods to research the situation of unpaid care worker in Indonesia. Using data from the Survei Tenaga Kerja Nasional – Sakernas (National Labor Force Survey) from 2005 to 2014, Utari found that unpaid care work of those aged 14 or more was still highly prevalent amongst female compared to its male counterpart, accounting for more than 55% gap between them. Most female unpaid care workers are the wife or daughter-in-law of the household head. Interestingly, females who are head of households spent a considerable amount their time doing care work, while it is highly probable that they were also the breadwinner in the family. Not only that, women had actively performed unpaid care work since they were very young, although the share of male population who did the very same work has continued to grow in the last 10 years.

However, it seemed that education helped narrow the gap of care work distribution between women and men, if not promoting gender equality. Postgraduate-educated men and women who carried out unpaid care work showed an apparent convergence trend. However, those who had no diploma at all had higher probability of being unpaid care worker and, and should they need any paid work, it was likely for them to end up in informal jobs which do not provide health insurance and social security.

The study does not intend to identify the depth of unpaid care work issues in Indonesia, but it has pointed out that there is a potential reduction of unpaid care providers amidst the growing needs of it. Utari also stated that time use survey is critically necessary in Indonesia to validate these findings for further research in the future. Participants of the seminar posed many questions about situation faced by Indonesian female migrant workers who has had to deal with care work. For the complete Q&A session, please refer to the link given in the sidebar.