The second FKP Seminar series hosted by SMERU Research Institute was held on 17 October 2017 at Cikini, Jakarta. Rendy A. Diningrat (SMERU Research Institute) presented his team’s recent study entitled “Designing Control Mechanism in the Era of Law No. 6 of 2014 on Decentralization Policy for Village”. This study was a mid-line report of an ongoing longitudinal research project that has started since November 2015 and will end in April 2018. There were 10 villages (desa) across Jambi, Central Java, and East Nusa Tenggara Provinces where the research was carried out.

Ever since the implementation of Law No. 6 of 2014 on Decentralization Policy for Village (hereafter UU Desa) or more specifically after the central government began to transfer money to each desa (dana desa), the number of uncovered corruption cases had surged during the past year, involving 139 people consisted of head of village, village apparatus and family. The Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW), a well-known NGO working on monitoring and reporting corruption cases in Indonesia, stated that the country suffered Rp30 billion of loss in 2017 alone caused by dishonest conduct of the use of dana desa. This high amount of corruption incidents at the lowest level of government administration invited reactions from various kinds of parties in the country: the national police signed a memorandum with Ministry of Village, Disadvantaged Regions, and Transmigration, and even the army was planning to also involve in controlling dana desa utilization.

The most crucial point of weaknesses in UU Desa implementation is associated with unprepared village administrative and limited surveillance from the people. This prompted Rendy and his team to look on this matter deeper. The study found that instead of investigating whether dana desa was properly used to empower the people, control mechanism was still focusing on writing end year reports for the district (kecamatan) in the correct format. If this practice continues, village people would be affected the most since the money they are entitled to for development cannot bring out the expected results.

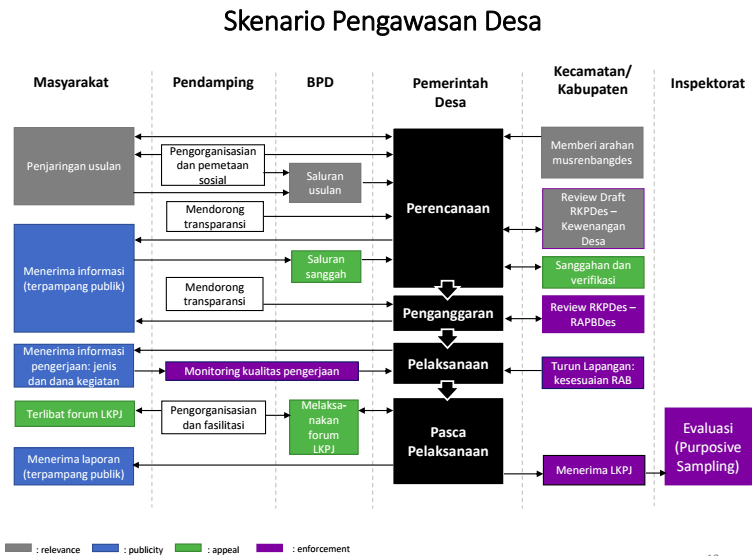

This study attempted to design a control mechanism given the conditions observed in the sample by applying theory of the accountability of reasonableness (Daniels, 1998). Monitoring and reporting process is basically classified into four functions: 1) Relevance, plans or budgets should meet people needs; 2) Publicity, the public is authorized to know the plans or budgets; 3) Appeal, challenging the decisions is necessary to make sure that plans or budgets are relevant; 4) Enforcement, ensuring the process conducted based on the agreement.

The illustration above shows the control mechanism corresponding to the accountability of reasonableness. It is apparent that village people is the most important group as it performs 3 out of 4 functions. The process begins with gathering proposals from the people that will be organized and socially mapped by village associates (pendamping desa) and channeled through Village Consultative Body (Badan Permusyawaratan Desa or BPD) to village government for planning purpose. The government is required to keep the people updated during the process of planning, budgeting, implementation, and post-implementation. However, this study suggests that any appeal to the village government should be directed first to the associate or BPD to avoid convolution.

This topic drew much attention from seminar participants. Although some comments were very technical, others also asked more fundamental questions, such as why some villages were successful in implementing UU Desa while the others not, and many more. Rendy, in return, invited the participants to be get involved in implementing other studies on the village fund distribution, use and reporting.